The Sisterhood changed the literary landscape in the ’70s. A new book traces how

Author Courtney Thorsson on “The Sisterhood,” a network of influential Black women writers who came together in late-1970s New York City.

POSTED IN Words

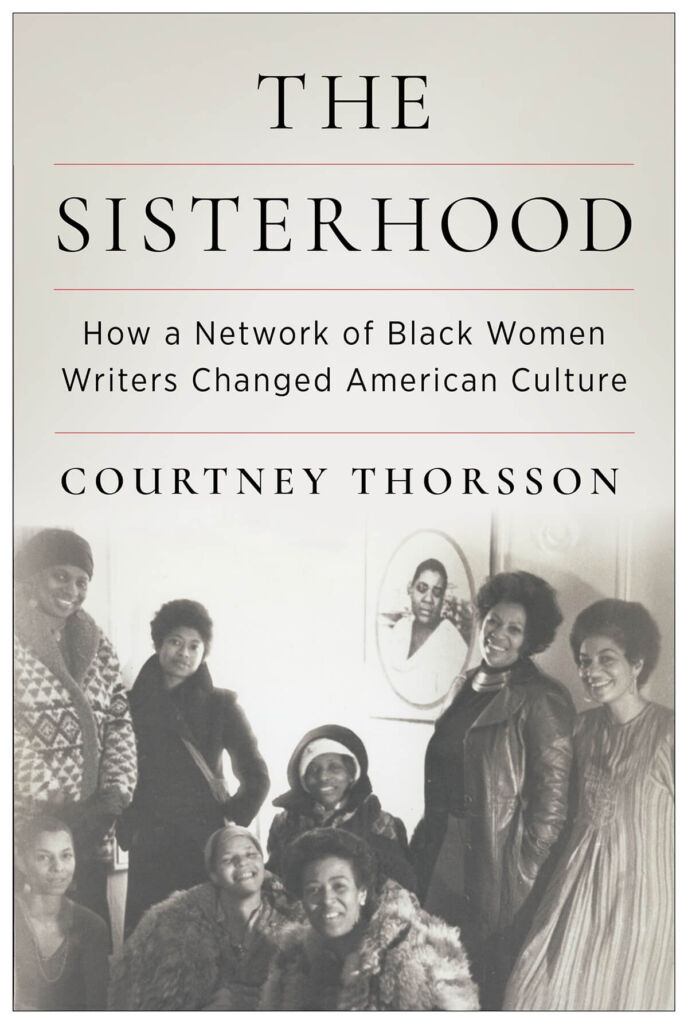

What stories can a photograph hold? For scholar Courtney Thorsson, a group photo of women gathered in a prewar apartment living room contained multitudes. When she first saw the photograph, she recognized some of the women immediately. There was Toni Morrison, Alice Walker and Ntozake Shange. Others, like June Jordan and Vertamae Grosvenor, she’d later come to know well while writing her latest book, “The Sisterhood: How a Network of Black Women Writers Changed American Culture.”

With this photo as a starting point (and as the cover of her book), Thorsson’s study explores how this group of women, aptly called “The Sisterhood,” created a generative space of support and community as they each pursued their writing careers in late-1970s New York City.

“The Sisterhood were part of an organized, active, collaborative effort to create what we now talk about as a Black women writers’ renaissance. That didn’t happen by accident,” Thorsson told ALL ARTS. “And it’s not just about one or two people, or one or two moments. It’s about the collaborative effort of Black women who intentionally came together to seek publication and publicity for Black women writers and to get Black women’s work and Black feminist ideas into books, magazines and the Academy.”

Over the course of the book, Thorsson makes it clear: She is not speaking for these women. “I’m often following the path that these Black women writers and intellectuals laid out by preparing their materials for future researchers, writers and scholars because they knew The Sisterhood was important when it was happening,” she said. “It’s not like I have to come along 40 years later and be the person who says, ‘Oh, you all did transformative work.’ They knew that then, and they know it now.”

Alice Walker, for instance, knew the importance of preserving a legacy for The Sisterhood. The author, who wrote the 1982 acclaimed novel “The Color Purple,” carefully inscribed the names of the sitters on the back of her copy of the photo, which now lives in the Alice Walker papers at Emory University’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library in Atlanta.

“The possibilities for research were unfolding as I was working on the project,” noted Thorsson, who combed through minutes from the group’s meeting while researching her book. As she began writing, libraries — like at Emory, or Princeton with Toni Morrison’s archive — were in the process of acquiring, cataloging and making available to researchers the personal archives of notable Black women writers, in particular those from The Sisterhood generation.

ALL ARTS spoke with Thorsson about her book, her process of rigorous research and some of the wisdom she has gathered from The Sisterhood. Below are excerpts from that conversation.

Note: Catherine Huff served as a research assistant to Courtney Thorsson on “The Sisterhood.”

What is a challenge you ran into while building out the book?

I am not an oral historian or a folklorist or a journalist, so conducting research and interviews with members of The Sisterhood and some of their interlocutors, or even just reaching out to people to request they meet with me — that was new. It even came down to asking myself, “How do you write good questions?”

I was not looking to interview somebody and then write up that interview for publication. I was looking to interview members of The Sisterhood to create primary sources for my interpretive literary history work.

Not to be cheesy, but it is clearly the case that you bring so much love to this topic. So even if you felt rusty with the interview questions, I think that comes secondary. What was most important to me was the passion and the intrigue that you were bringing to the text. That’s why, in my eyes, it’s such a great read.

I’m sure, as it’s clear to you, I demonstrate my love through rigor. It’s the seriousness of the research and the knowledge that is the way I show what I love. It is serious intellectual labor with a profound love for African American women’s writing.

You know, I write about all kinds of different things, but I don’t write about texts that I don’t think are beautiful and worth everybody’s time, just like I wouldn’t put a text on a syllabus that I don’t think is important, beautiful and worth everybody’s time.

My role is to offer a sympathetic, interpretive cultural history that’s about the effects of their collaborative labors.

And we’re having this conversation even in Banned Books Week. When the debates over College Board and A.P. African American Studies and of public schools banning specific authors — I mean, there are like four Sisterhood authors on that list.

Toni Morrison, for instance, is massively important to literature and history. And most people already know that, right? But the stakes of saying June Jordan, Audreen Ballard or Cheryll Y. Greene are also incredibly important to literary history and transformed what we actually read, think about and teach. Those stakes couldn’t be any higher than they are right now.

On that note, what are some works that you might suggest from these writers that are maybe overlooked or less appreciated?

There are many examples, but I’m going to confirm we are still getting new work from many of these women. Patricia Spears Jones has a brand new volume of poetry called “The Beloved Community,” so I highly recommend her.

I would say [Margo Jefferson’s] two memoirs, “Negroland” and “Constructing a Nervous System,” which are both recent and have really kind of transformed the possibilities for memoir.

I would say that June Jordan’s essays collected in the 1980 volume “Civil Wars” should be taught as commonly as Toni Morrison’s collected essays or essays by Ralph Ellison or Richard Wright in terms of our understanding of American literature.

The wisdom of The Sisterhood is a resource for students, writers and activists who are imagining and making a better world right now. What wisdom can we take away from these women now, in 2023, especially for your students who are reading these works with you for the first time?

Is there anything worth doing if not collaboratively? It’s not done alone. If it looks like it’s done alone, you’re missing a lot of the picture. Movements for liberation in the United States have long been about Black women’s collaborative works, not charismatic individual male leaders.

The things that these women, like June Jordan, Toni Morrison and others, dreamed of in the late-60s and early-70s are things we should dream of again. Young people have never lived in a time when there was regular discourse about free college education for everyone. Free daycare for every child under five. I mean basic human rights. Housing, health care, a true social safety net.

I’m a part of a broad swath of people who understand that literature is essential to the work of liberation. Any movement for liberation requires the power of imagination, like poetry, music, visual arts and writing.

You’re finished writing “The Sisterhood.” What’s next?

Right before the book comes out, I will get to participate in the Phillis Wheatley Poetry Festival [Nov. 1-4], which is celebrating its 50th anniversary at Jackson State University. It commemorates the 1973 Phillis Wheatley Poetry Festival, which is where Alice Walker and June Jordan really solidified their bond, and is where Alice Walker read essays from “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens” for the first time in 1973. Alice Walker will be a keynote speaker at those 50th anniversary commemorative events.

“The Sisterhood” publishes Nov. 7. For more information, visit the book’s page on Columbia University Press’ website.

Members of The Sisterhood included: Zita Allen, Audreen Ballard, Rosemary Bray, Nancy Clare, VèVè Amasasa Clark, Andaye De La Cruz, Audrey Edwards, Phyl Garland, Vertamae Grosvenor, Rosa Guy, Jessica Harris, Joan Harris, Margo Jefferson, Patricia Spears Jones, June Jordan, Audre Lorde, Paule Marshall, Nana Maynard, Susan McHenry, Madeline Moore, Toni Morrison, Patricia Murray, Pamela Roach, Sheila Rush, Ntozake Shange, Lori Sharpe, Donna Simms, Alice Walker, Diane Weathers, Renita Weems and Judith Wilson.

Note: This interview has been lightly edited.

Top Image: June Jordan, Alice Walker, Lucille Clifton and Audre Lorde singing at the Phillis Wheatley Poetry Festival, 1973. Photo: Roy Lewis.